General Information

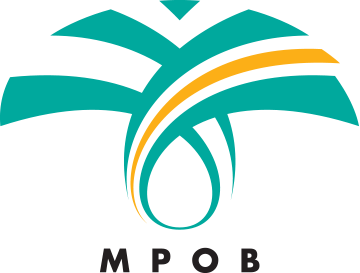

Rhynchophorus palmarum is one of the important pests on commercial palm plantations, Cocos nucifera, Elaeis guineensis and sugarcane, and on ornamental palms. The larvae feed on the growing tissue in the crown of the palm, destroying the apical growth area and causing death of the palm. Economic damage depends on the palm species and on the number of larvae infesting the plant. Populations of 30 larvae are sufficient to destroy an adult coconut palm.

R. palmarum is also the vector for the red-ring disease nematode, Rhadinaphelenchus cocophilus. Palms infected with the red-ring nematode usually die within a few months (2-4 months). Up 10%-15% losses is incurred annually on infested plantations. Heaviest losses occur at the end of the wet season and in the first 2 or 3 months of the dry season. The characteristic symptom of infection is a red, concentric ring that extends throughout in the stem. Other visible symptoms include decline in fruit production, premature nutfall, yellowing and aging of fronds, and the “little leaf syndrome” where fronds experienced stunted in growth. Red streaks may appear in the petioles, and the roots may turn orange to faint red and become dry and flaky. There is no known treatment for the red-ring disease.

The weevil ingests the nematode while it is still in its larval phase. As many as 10 000 R. cocophilus juveniles can be harboured by one weevil. Adult female weevils deposit the nematodes during oviposition, usually at the leaf axils or internodes. Nematodes can also be carried on the bodies of the weevils and enter hosts through wounds. Once inside, the nematodes colonise the stems of palm trees, leaf petioles and occasionally in the roots, start feeding and reproducing in palm tissue. The diseased palm starts wilting and eventually dies. The cycle repeats as the weevil larva and pupa co-exist with the nematodes in the host, and are spread once the adult weevil tunnel through the dying host and disperse to healthy palms. The weevils follow the scent of kairomones to locate potential host palms. The kairomones are released through injury wounds or cuts on palms.

The abundance of adult palm weevils changes with seasons. In Trinidad, populations increase from the end of the rainy season throughout most of the dry season in coconut plantations; while in Brazil, Costa Rica, Honduras and Colombia, in the dry season in oil palm plantations.

R. palmarum are most active during dusk and dawn. At other times, the weevils seek refuge in dark, moist places e.g. plant debris. Local spread is through flights, but long distance spread is mostly through movement of infected plants for planting of palms or hitchhiking on vehicles/machineries.

Distribution

Mexico, Central and South America and the southernmost Antilles.

Detection and Inspection

R. palmarum primarily attacks the apical region of palm crowns, and larvae remain inside the galleries they build. Therefore, the pest can only be detected when damaged plants start to die, or by using pheromone-baited traps.

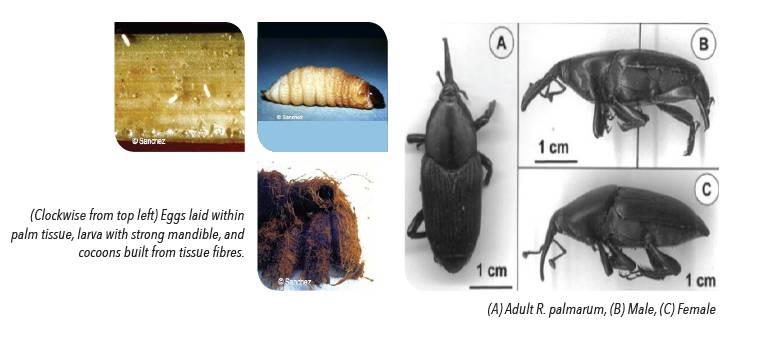

ADULT

Adults have a black, hard cuticle and possess the characteristic elytra of Coleoptera, protecting the abdomen when closed. They measure 4-5 cm in length and are approximately 1.4 cm wide, weighing 1.6-2 g. The head is small and round, and has the characteristic long, ventrally curved rostrum.

PUPAE

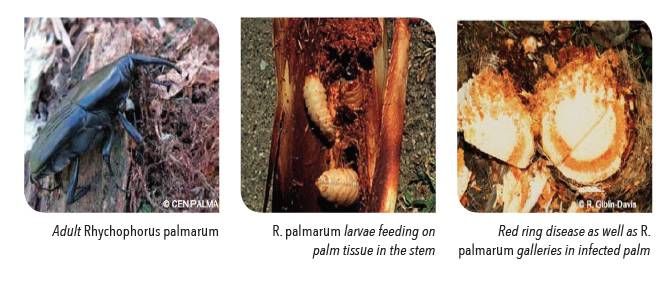

Exarate and light brown. The abdomen continuously makes undulatory movements when distrubed. Pupae inhabit a cylindrical-ovoid closed cocoon 7-9 cm long and 3-4 cm in diameter, built in a spiral with plant fibres.

LARVAE

Cream white and can measure from 3-4 mm to 5-6 cm long. The larvae are cannibalistic; possess sclerotized mouth parts with strong mandibles. Move to ends of their galleries in the trunk, floral rachis or leave stem before pupating.

EGGS

Eggs 2.5 x 1 mm, located individually 1-2 mm inside soft plant tissue, white with rounded ends.

Prevention and Control

PHYTOSANITARY

It is listed as an EPPO A1 quarantine pest. The import of germplasm material (seeds, pollen, tissue culture) must be accompanied by an import permit issued by or on behalf of the Director-General of Agriculture for Peninsular Malaysia (including Labuan), or the Director of Agriculture for Sabah, and a phytosanitary certificate issued by an authorised official from the country of export. The import conditions are available upon request from the Plant Biosecurity Division Malaysia. All consignments are subjected to inspection by the Agricultural Department prior to clearance by Customs. Germplasm material imported from high risk areas should be sent for third country quarantine before arrival onto Malaysian shores. The import of alternative host plants e.g. Metroxylon sagu, Phoenix dactylifera, Saccharum officinarum from infested areas should be enquired with DOA.

CULTURAL CONTROL AND SANITARY METHODS

The most widely used control method is the capture of adults with traps. Baits using either i) rotting plant materials, such as palm tissue, pineapple and sugar cane, or ii) pheromones can be used. The traps are with pesticide (e.g. methomyl, triclorfon and pirimifos-ethyl) at the bottom to eliminate captured weevils. Yellow traps seem to be more efficient than those of other colours.

Further reading

- Bronson, C H (2010). Pest Alert: The Red Ring Nematode, Bursaphelenchus cocophilus. DACS-P-01748.

- CABI Invasive Species Compendium (2015). Rhynchophorus palmarum (South American palm weevil). Url: http:// www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/47473.

- Giblin-Davis, R (undated). Biology and management of palm weevils. University of Florida/IFAS. Fort Lauderdale Research and Education Centre.

- Howard, F W; Moore, D; Giblin-Davis, R M and Abad, R G (2001). Insects on Palms. CABI Publishing: UK. 400 pp.

- Miguens, F C; De Magalhaes, J A S; De Amorim, L M; Goebel, V R; Le Coustour, N; Lummerzheiwm, M; Moura, J I L and Costa, R M (2011). Mass Trapping and Biological Control of Rhynchophorus palmarum L.: A hypothesis based on morphological evidence. Entomo rasilis, 4(2): 49-55.

- OEPP/EPPO (2005). Data sheets on quarantine pests: Rhynchophorus palmarum. Bull. OEPP/EPPO Bull. 35: 468-471.